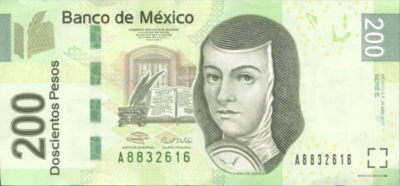

God Gave Women Intellect to Use It: Catholic Nun and Feminist Icon Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Hailed as the first feminist of Latin America, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, OSH, was a 17th-century Mexican nun known for her theological writings on conscience, free will, and women’s education. Conscience’s managing editor Kate Hoeting spoke with Theresa A. Yugar, a leading scholar in the study of Sor Juana’s feminist thought.

Kate Hoeting: Let’s start by putting us in Sor Juana’s world. What were the key theological and political contexts of the Mexico she knew?

Theresa A. Yugar: Sor Juana was born in 1648 — more than 130 years after the Aztec Empire had been destroyed — in what is now known as Mexico. Her world was a product of that colonialization process.

Both the church and Spain had political authority over New Spain, and they were all men. People like the Spanish nun St. Teresa of Ávila wrote about having mystical experiences during prayer, which suggested women could claim direct authority to God. The church opposed this. They wanted women to either be married or to be the bride of Christ, because in both situations, men and the church could govern women’s authority. They didn’t want women to be thinking independently of the clerical establishment.

How did Sor Juana’s upbringing influence her?

Sor Juana lived in a society controlled by men, but she grew up in a family of women. Her mother, Doña Isabel Ramírez, was Criolla, meaning she was the daughter of a Spaniard born in New Spain. Doña Isabel had four daughters with two men — so Sor Juana was illegitimate according to the clerical church — and chose not to marry. It was not acceptable in Sor Juana’s society to be independent, but her mother was. And although Doña Isabel could neither read nor write, she managed a hacienda.

This patriarchal culture said women were foolish and irrational, yet Sor Juana knew from experience that this was not the case. She could draw from her experience — her truth as a woman — to dispute the church’s argument that women were incapable of reason.

Then Sor Juana became a nun. So just like her mother, Sor Juana managed to avoid getting married in a society where becoming a wife was the dominant expectation for women.

That’s right. I think that Sor Juana is a reflection of her mother. I think Sor Juana was sitting at the table listening to her mother, and that her mother had opinions. Opinions are essential to Sor Juana’s understanding of Christianity. For her, there was room for different opinions. Yes, there were official church teachings and doctrines. There was the Hebrew and the Christian Testament. Yes, there was Jesus. But if you could articulate and support your opinion well, there was room for it.

"Opinions are essential to Sor Juana’s understanding of Christianity. For her, there was room for different opinions."

— Theresa A. Yugar

But Sor Juana didn’t think just any old opinion was good, right?

Yes, that’s right. To her, it’s important to know what you are talking about when you critique things. She drew from church fathers, Scripture, and secular sources.

A great example of this is La Respuesta (The Answer), which was a theological treatise she wrote to criticize the Portuguese Jesuit António de Vieira, who argued that God’s greatest gift was God’s love for human beings. But Sor Juana said that the greatest thing God did was withhold God’s love in order to allow them to exercise free will. She says that free will is an important part of being Christian.

Did Sor Juana face any repercussions for critiquing a Jesuit?

Bishop Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz asked her for a copy, and she said he could if he only used it for personal prayer. Well, he published it. And he wrote his own little letter critiquing her. He said that it would be better for her to study sacred works if she cared about her salvation. This upset her. She penned a response to the bishop’s assertion that women should not read and write, that they’re subordinate to God. She wrote about the primacy of conscience. She told the bishop that he did not have the power to judge her salvation. Only God does.

It sounds like according to the church hierarchy at the time, the main qualification for being educated was being a man. How do you think Sor Juana’s idea of education differed from that of men at the time?

She drew from Greco-Roman myths, Aristotle, Plato, Thomas Aquinas, Athanasias, Jerome, St. Paul, and more. She drew on science, on Christian tradition, and on the Bible to inform the way that she understood Catholicism.

She also looked at plants to understand God’s nature. She knew Nahuatl, Latin, and Spanish, since she lived with Spanish, non-Spanish, and Indigenous people. That’s how she understood there are many different ways of knowing. She says that her desire to learn was an impulse given to her by God.

Experiential wisdom was just as important as academic knowledge for Sor Juana. She watched her family’s experience with men, not just her mother’s, but also her two older sisters’ who were both abandoned by men. She said it was better for women to be educated by women, because being educated by men could cause innumerable harm and women could be violated. She kept her two younger stepsisters in the convent with her so that they wouldn’t be abused before they got married. She knew that men were not these elevated beings.

She found that the men in her spheres were not all that educated. In La Respuesta, Sor Juana wrote that Aristotle could have written more if he knew how to cook.

"Aristotle could have written more if he knew how to cook."

— Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

When you talk about her theological perspectives on conscience and how to form a good conscience, it sounds like verbatim canon law. Canon 748 says, “All persons are bound to seek truth in those things which regard God and his church, and by virtue of divine law, are bound by the obligation and possess the right of embracing and observing the truth which they have come to know.” So in my reading, all people have a duty to seek their own truth through God and church, and we all have an obligation to observe and respect that truth.

Prophetic!

That’s what Aquinas says too! He says that conscience is connected to both reason and will, and that it is possible for sin to exist in conscience, but at the end of the day “He who acts against his own conscience always sins.” In her time, Sor Juana has the hierarchy saying that she’s wrong, that what she’s saying is heretical. And yet today, the things she says are in canon law! They’re in the catechism!

That’s why she was a feminist. She was way ahead of her time. And sadly, the challenges she faced then are the same as what we’re facing now as women in the church.

What does Sor Juana mean to you?

For me, personally, she’s a role model. She’s a source of inspiration. As a Latina feminist theologian, I’m fascinated that I didn’t learn about her during my 16 years of Catholic education. I see myself in Sor Juana, and it saddens me that there are so many women in the church who are serving God, and yet we’re just not respected. Church doctrine still undermines us. We’re still the subordinate sex.

But there are still prophetic people like Roy Bourgeois, who was dismissed from the priesthood for participating in women’s ordination in 2008. We have Catholic sisters like Margaret Farley, Elizabeth Johnson, Joan Chittister, and Ivone Gebara. Sor Juana spent 25 years as a nun. They silenced her. Recently, the church silenced Ivone Gebara because she said that the church cares more about the planet than women.

We have seen that too at Catholics for Choice. Pro-choice Catholics have faced immense pressure and continue to do so. But we know that while our work is morally complex, people must follow their God-given conscience, even when there are a multitude of perspectives on an issue.

Sor Juana would respect that there are different opinions and perspectives. What she didn’t tolerate was illogical reasoning. She was a woman, and women should not have been writing. She said that people had free will. She dared say that she, too, was a source of authority in the church.